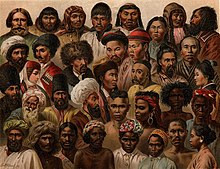

Ethnicity and race

Ethnicity is used as a matter of cultural identity of a group, often based on shared ancestry, language, and cultural traditions, while race is applied as a taxonomic grouping, based on physical or biological similarities within groups. Race is a more controversial subject than ethnicity, due to common political use of the term. Ramón Grosfoguel (University of California, Berkeley) argues that “racial/ethnic identity” is one concept and that concepts of race and ethnicity cannot be used as separate and autonomous categories.

Before Weber (1864-1920), race and ethnicity were primarily seen as two aspects of the same thing. Around 1900 and before, the primordialist understanding of ethnicity predominated: cultural differences between peoples were seen as being the result of inherited traits and tendencies. With Weber's introduction of the idea of ethnicity as a social construct, race and ethnicity became more divided from each other.

In 1950, the UNESCO statement "The Race Question", signed by some of the internationally renowned scholars of the time (including Ashley Montagu, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Gunnar Myrdal, Julian Huxley, etc.), stated:

"National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups: and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connection with racial traits. Because serious errors of this kind are habitually committed when the term 'race' is used in popular parlance, it would be better when speaking of human races to drop the term 'race' altogether and speak of 'ethnic groups'."

In 1982, anthropologist David Craig Griffith summed up forty years of ethnographic research, arguing that racial and ethnic categories are symbolic markers for different ways that people from different parts of the world have been incorporated into a global economy:

The opposing interests that divide the working classes are further reinforced through appeals to "racial" and "ethnic" distinctions. Such appeals serve to allocate different categories of workers to rungs on the scale of labor markets, relegating stigmatized populations to the lower levels and insulating the higher echelons from competition from below. Capitalism did not create all the distinctions of ethnicity and race that function to set off categories of workers from one another. It is, nevertheless, the process of labor mobilization under capitalism that imparts to these distinctions their effective values.

According to Wolf, racial categories were constructed and incorporated during the period of European mercantile expansion, and ethnic groupings during the period of capitalist expansion.

Writing in 1977 about the usage of the term "ethnic" in the ordinary language of Great Britain and the United States, Wallman noted that

The term 'ethnic' popularly connotes 'race' in Britain, only less precisely, and with a lighter value load. In North America, by contrast, 'race' most commonly means color, and 'ethnics' are the descendants of relatively recent immigrants from non-English-speaking countries. 'Ethnic' is not a noun in Britain. In effect there are no 'ethnics'; there are only 'ethnic relations'.

In the U.S., the OMB states the definition of race as used for the purposes of the US Census is not "scientific or anthropological" and takes into account "social and cultural characteristics as well as ancestry", using "appropriate scientific methodologies" that are not "primarily biological or genetic in reference".

Comments

Post a Comment